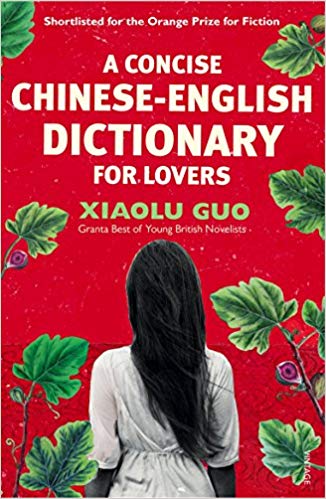

Title: A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers

Author: Xiaolu Guo

Published: 2008

Publisher: Random House

This book is not strictly chick lit but it has two of the elements – a romantic relationship (although not a quest for a partner per se) and a Bildungsroman trajectory. It also has a characteristic that while not indicative of the gender as a whole, may be classified as a sub genre – the East West encounter.

Our protagonist with the unpronounceable (to non-Chinese people) name – Zhuang Xiao Qiao – travels from a small town in China to London to learn to speak English. There she encounters the strangeness of the West which she gradually comes to embrace (somewhat) via the mediation of a Western man.

In this, the novel is similar to Shanghai Baby, which I will write about later, in that it proposes the Western man in some sense as the initiator into sexual (and by implication cognitive) liberation. This novel is different, however, in that said Western man is presented as the yin (roughy dark/passive/female principle) and the Chinese woman as the yang (light/active/male principle).

There is also an acknowledgement of the lopsided nature of the cultural initiation process. The older Western man imparts knowledge but rarely expresses curiosity in the younger Asian woman’s culture, expressed in her frustrated cry: “You never ask me!”

The novel does somewhat fail the Bechdel test. Written in the second-person and centering on one potent romantic relationship, maybe Guo can be forgiven for basically having her protagonist almost exclusively converse with one man, but it did strike me as weird that one her solo trip to Europe all her encounters were with men. Or is this what happens when pretty young women travel alone and naively proceed with conversations (and more) with strangers?

Because the novel is a journey in language as well as cultural accumulation, it is written in the distinctly broken English of the Chinese person. Thus, unlike The People’s Republic of Desire which presents itself as seamless English text, this novel speaks in the voice of the linguistic outsider and the unsophisticated small town girl and thus rings truer.

Novels which turn on the East-West encounter can descend into cliche but this one stops short and the stumbling language is one reason for this. When non-native speakers use a language there may be a lot of errors, yes, but there is also the possibility for intended or unintended defamiliarisation. This may be a part of the success of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. It is also why I used to tell my students not to strive for so much perfection in English that they strip the Cantonese out of their speech. That in trying to translate too perfectly, something precious may be lost. That I have never come across a seamless translation of “gaa yau” (“add oil”) and maybe that is as it should be.

In fact, the novel also highlights this in conversation on Xiao Qiao’s birthday. “You are funny,” the Western men tell her and her Japanese friend. The women point out that they don’t mean to be, that the humour and the straighttalking is the unintended consequence of their linguistic poverty (in English).

“Quiche, q-u-i-c-h-e. I can’t believe it when I am swallowing this piece of shapeless hot stuff. Such an ambiguous piece of food. Totally formless. I wonder about what my parents would say if one day they come to this country, and they eat this. My mother probably will say: ‘It is like eating something from other people’s mouth.’ And my father will say: ‘It must be left from earlier meal so they re-cook it but inside are already messed up.’ I will agree with my father: it is a piece of big mess indeed. You tell me it is actually from France and I don’t believe you. I think the English are too ashamed to acknowledge it is their food. So they say it is French to defend themselves.”

My love of quiche could not stop me from giggling madly. Apart from the humour, the writing touched me in some primitive way. For the past five years or so possibly as a result of aging and the diasporic life, I find a special place in my heart for the diction of home – the mixing of Hindi and English exemplified by Anuja Chauhan’s work, the patterns of speech of the aunties of the Bombay suburb I grew up in and now I realise, the particularities of the Chinese people speaking English. Just goes to show how the Chinese has become so embedded in my idea of home.

One thought on “A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers”