Title: Red, White and Royal Blue

Author: Casey McQuiston

Published: May 2019, St Martin’s Press

One of my motivations in doing my PhD was to answer the question: is a feminist chick lit novel necessarily an oxymoron? (In my 20s, I would have wanted to write a novel myself that positively answered that question. By my 30s, I had realised this was unlikely to happen, and I contented myself with critique.)

The novels I ended up studying didn’t answer the question with an unequivocal yes, but by then my question had shifted.

Red, White and Royal Blue’s answer to the question is a resounding yes. Not only is it possible to write enjoyable feminist chick lit, it is possible to write enjoyable feminist queer chick lit.

Alex Claremont-Diaz is the First Son. He and Prince Henry, the spare in the British royal hierarchy, are antagonists, until they’re forced to make nice, and then it turns out that the old trope “he’s mean to you because he likes you” is true.

The novel is very Gen Z in that it ticks all the diversity boxes. The president, a divorced single mom, and her chief of staff are women.

Alex is half Hispanic. His father is also a senator, and is supportive of his former wife’s campaign.

His best friends are his sister June, who wants to be a journalist if being the president’s daughter wasn’t a liability, and the vice-president’s daughter Nora, a math genius. He has been linked to Nora romantically, and the two are content to feed the rumours.

Henry is the rebellious second son, who doesn’t quite fit in, but yet is very British. He’s not ginger, but the family dynamics are very Windsor. His grandmother, the queen, is hell bent on preserving the family’s legacy, and his elder brother has bought into it. His mother is fragile and has retreated into her shell after their father’s death. He is close to his younger sister, but she has her problems.

Alex and Henry’s relationship seems to have been scripted in fan-fiction, and of course the novel references this. They are star-crossed lovers. While their countries are allies, this transatlantic relationship has geopolitical implications. Alex’s mother is up for re-election, and obviously, an openly gay prince is no-no for the royal family.

Once Alex and Henry admit their feelings for each other you wonder how this can all end.

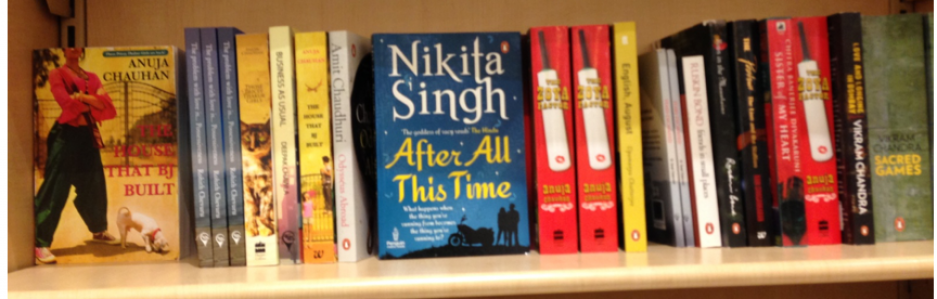

It turns out that the larger romance was not individual but national. In my study of Anuja Chauhan’s novels, I argued that the larger fantasy in the novels is of a certain idea of the nation, one that embraces diversity. The romantic coupling and the journey – in space and time – towards it is symbolic of this.

Something similar happens in Red, White and Royal Blue. Throughout the novel, there is mention of Alex’s binder, a study of the state of Texas’ voting patterns. Texas is the Claremont-Diaz home state; it is also a state that has been staunchly Republican.

The United States has come a long way. But the turning of Texas from red to blue – the colours of the title take on many shades of meaning here – would signal a true turning of the tide. Would Texas elect a divorced, single mother as president if her son was gay? That, my dears, is really the question at the heart of the novel’s culmination.