I’m a great fan of Anuja Chauhan’s romance fare, which formed a central part of my thesis on Indian chick lit, so I was a tad disappointed when she turned to the detective genre. Nevertheless, in her portrayal of the typical gymkhana in Club You to Death, her characteristic eye for the idiosyncrasies and types of Indian society was very much in evidence, and in ACP Bhavani Singh, she created a detective who I wanted to see more of. There was even a romance plot, although it may not have turned out entirely satisfactorily.

It took her three years to get out the sequel, The Fast and the Dead. By now, she has been ensconced in Bangalore for several years, and so felt ready to set a novel in the city, rather than in her literary comfort zone of Delhi. My initial thought was that her attempt at conveying the Kannada-speaking milieu was too try hard, but as her scope broadened slightly, it began to work for me, although she probably got some cultural nuances wrong.

The action is largely set in one lane, Habba Galli, off MG Road. which becomes her microcosm of India. Because I have realised this is really Chauhan’s project, irrespective of genre. She is here to underline the diversity of India, not in saccharine but in affectionate and quasi-absurd terms, a reinforcing of a Nehruvian ethos that is now under threat, if not entirely the material of nostalgia.

A sonorous aarti rises from a small Manjunath temple and, at the same time, an azaan warbles up companionably from the minaret of the green-domed dargah opposite, reminding Jhoom of why, power cuts notwithstanding, she loves her neighbourhood.

While the obvious political rivalry in India today is Hindu/all else (but particularly Hindu/Muslim), Chauhan zeroes in on a very contemporary urban Indian phenomenon – the neighbourhood wars over street dogs. This is ostensibly the source of the conflict that leads to murder, though in the end, it turns out that, as is often the case, it comes down to the rot at the heart of a family. There is the “pilla party” who feeds and cares for the street dogs – the descendants of a matriarch called Roganjosh – and those who see them as a menace.

On one side is the veterinarian Jhoom Rao (“rich, Brahmin, forbidden, unattainable”) and her eccentric feminist mother Jaishri, once well-heeled but now fallen on hard times, Ayesha Sait, the mother of Bollywood star Haider who has long had the hots for Jhoom, and Mehta(b), the Kashmiri carpet seller. On the other side is mongrel-hater-in-chief nouveau riche Marwari jeweler Sushil Kedia, and Doodi Pais, a mad old woman with a gun. Given that in my own building in Bangalore, there is a running feud over the tatti of pooches in the building compound, Chauhan’s choice of metaphor seems particularly apt.

When Tiffani, the Weimeraner puppy that the Kedia scion, Harsh, gifted his wife Sona, “grew into a fine young lady ready to socialise with males of her own class” and brought forth not “the slender silver-grey golden-eyed litter the Kedias had been expecting” but “a plump snub-nosed brood in variegated-patches of brown, yellow, black and white”, evidence of (gasp) love jihad, all hell broke loose.

The dogs themselves are symbols of a disruptive force that cuts across class barriers.

We think it is because stray dogs have a total lack of respect for established human hierarchies – they tend to grovel before beggars and bark at billionaires

ACP Bhavani Singh

I disagree. My own observation is that stray dogs often tend to adopt the class system of the humans with which they live, barking at poor, shabbily dressed people and letting the well-heeled pass with a twitch of an eyebrow. And that the furore over these dogs in communities is also due to an overdeveloped middle class sense of hygiene and fear of animals, possibly dating to childhood. Bhayani’s thesis is interesting nonetheless.

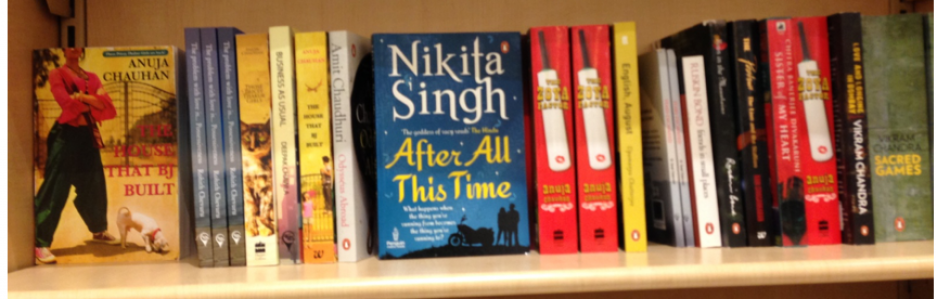

Meanwhile, in the Jhoom-Haider romance are shades of Bonu-Samar pairing of The House that BJ Built, complete with shades of Bollywood and unrequited crush vibes, but also of the “love jihad” that Chauhan so delectably presented in Battle for Bittora. This plotline underscores one vector of Indian stratification – the religious one- just as the dogs underline the class divide.

The action starts on Karva Chauth, a north Indian festival that curiously seems to have been taken up with gusto in this South Indian lane. And it is here that the dissension at the heart of the Kedia family becomes clear. Sushil Kedia is mean to his wife and children, and his daughter-in-law is not amused and subtly makes this known. On Karva Chauth, his wife has her rebellion, not only putting a teeka on the dog Roganjosh, but breaking her fast to feast on a seven-course meal. The next morning Sushil is discovered dead, a gunshot wound to the head, in his studio.

Enter Inspector Bhavani Singh who is on an “annual honeymoon” with his wife English-teacher wife Shalini and conveniently staying in an AirBnB down the road, run by Krishna Chetty, childhood buddy of Haider Sait with political aspirations and son-of-the-soil pride, who bears traces of the slightly shady Steesh in The Pricey Thakkur Girls.

Chauhan does not entirely gloss over the dangers of the religious fanaticism that has reared its head in modern India. In the quintessential Indian aunty, Mrs Charu Tomar, she gives us one of the possible psychological underpinnings of the phenomenon at the individual level: insecurity.

But the trouble is that being fat as well as poor made her unhappy, so she became holy, and being holy made her narrow-minded, judgemental and bossy.

Mrs Tomar seems harmless, but she is a subscriber of a dangerous ideology couched in the ranting of a busybody:

Arrey, Gandhiji’s own sons pleaded with the government to spare the life of his assasin, Nathuran Godse! They knew Godseji was in the right and Gandhiji was in the wrong!”

And when news of the murder leaks and the lane attracts a media circus, Haider’s director friend advises him to move his mother away because at such times, it is less than ideal to be Muslim.

Both Sushil Kedia and Mrs Tomar are unpleasant characters and one can’t feel too sorry about their fates. Eventually, ACP Bhavani Singh has his day, and the identity of the murderer did come as a surprise to me.

And while this might be the culmination of the novel, it actually ends on a happier note, when the disruptive power of love wins outs. Here again, as in Battle for Bittora, love not only triumphs but by harking back to past innocence – a love that began over a girl saving a street dog – holds out the promise of a nation united across differences.

Best lines

“He’s become like that Bheeshma pitamah, Christian version”

“She’s started making evening appearances on her balcony nowadays, like she’s the Pope or Shah Rukh Khan, and heckling the dogs till they bark at her”

“Sparshu, a human tapeworm who needs to eat every forty minutes”

PS: Club You to Death is out on Netflix as Murder Mubarak. It’s got a star cast (Karisma Kapoor, anyone?) and is pretty good, better in fact than the screen versions of any of Chauhan’s other novels, but while the casting was spot on, I’m not happy with how Bhavani was portrayed as a little kitsch while the old money of the club came across as one-tone Punjabi loudness.

Have you watched it? What did you think?