I came slightly late to the Made in Heaven party, but like everyone else I was besotted and struggled with the binge instinct. Since I started watching it on a weekday, I basically could allow myself only a couple of episodes a night in the interest of not sleepworking the next day.

Okay, for those living under the proverbial rock, Made In Heaven is an Amazon Prime series set in Delhi, India, created by Zoya Akhtar and Reema Katgi. It follows wedding planners Tara Khanna (Sobhita Dhulipala) and Karan Mehra (Arjun Mathur) as they craft the formal unions of young Indians and their families. Each episode features a wedding to be planning, distinguished by its own brand of crazy.

Employing marriage as the theme allows for the exposition of the wealth-fuelled proclivities of new India’s elite – weddings have been said to be a recession proof industry, and this is particularly so in India where the celebration of marriage is a display of social status. This is remarked on in the very first episode when a rival wedding planner suggests to the parents of the groom, who will presumably fund the extravaganza and who are as important as the couple exchanging vows, that the wedding is a vehicle to brand themselves the new royalty.

The wedding theme also, however, provides scope to explore the less heavenly aspects of marriage from the get go: class differences, the generation gap that must be dealt with because of the overbearing presence of parents, especially of the groom, in a new couple’s life, dowry demands, infidelity.

And then there’s Tara and Karan themselves. Like the bride in the first episode, Tara would be seen by the elite class that her husband belongs to as a gold digger (more on this later). To counter this, she has to present the seamless facade of perfection all.the.time. Despite this, the cracks in her marriage begin to widen.

Karan is a gay man living a sexuality active life before the Supreme Court struck down Article 377 of the Indian penal code that effectively criminalised homosexuality. Despite his best efforts to pretend that one can live as one likes despite the social and legal censure, he becomes caught up in a dangerous web.

Since I can’t spend most of my day in front of the television, I felt the need to extend the feeling of the series somehow. And that’s when I decided to reread The Wedding Photographer by Sakshama Puri Dhariwal.

…

Before I go on, I must say I absolutely enjoyed this novel. While I was reading it – for the second time – I had a sappy smile on my face that had my husband grab the book out of my hands and peruse the pages to figure out what I was grinning about, then tease me about the rubbish I read. Classic, bringing to mind all those romance reader studies from Janice Radway to Radhika Parameswaran. No wonder I had to get a PhD to put a stamp of legitimacy on my “trivial” pursuits. When I am challenged about my choice of topic, I simply point out that the financially astute Hong Kong government paid me handsomely to work on this for three years and leave it at that.

Back to the novel, I enjoyed because it is well written. Not only does it skilfully employ all the genre tropes that have hit the right buttons for readers since the 19th C, Puri has a flair for snappy dialogue not just between the central pair but also the kind of online chat exchanges and verbal repartee between friends.

The novel’s protagonist Risha Kohli is the wedding photographer of the title. On a flight back to India from Los Angeles, she finds herself seated next to Arjun Khanna, the scion of a real estate empire, whose sister’s wedding, it turns out, Risha is slated to photograph. They are both attracted to each other, but this being a romance – I would tend not to classify it as chick lit although it ticks most of the genre boxes for reasons I will go into later – there are obstacles to their throwing off their clothes and shagging each other coupledom.

The obstacles, as they appear, are pretty stupid:

- Arjun is suspicious of journalist and is miffed that he didn’t know she was one

- His mother asks Risha to take photos of him with another woman so Risha assumes he has a girlfriend even though he explodes at his mother when he realises what’s going on and stalks off and there’s zero chemistry between him and the other woman

- Risha’s gay BFF Rishabh (okay, there might be a reason why their names are so similar but it evades me) tries to make Arjun jealous by pretending to be her boyfriend and he falls for it even though his grandmother can see through it

- Arjun asks Risha if Rishabh is her boyfriend and she gets upset and storms off

- Then when a Rishabh’s status as bestie-not-boyfriend is made clear, she once again thinks Arjun into the other woman because he let her win at Tetris

- The biggie is when the wedding photos are leaked thus confirming Arjun’s worst suspicions

It’s possible that I’m just a jaded old aunty but these problems seems self-made and silly, except the last one. Maybe twenty-somethings are actually this insecure and I just don’t remember.

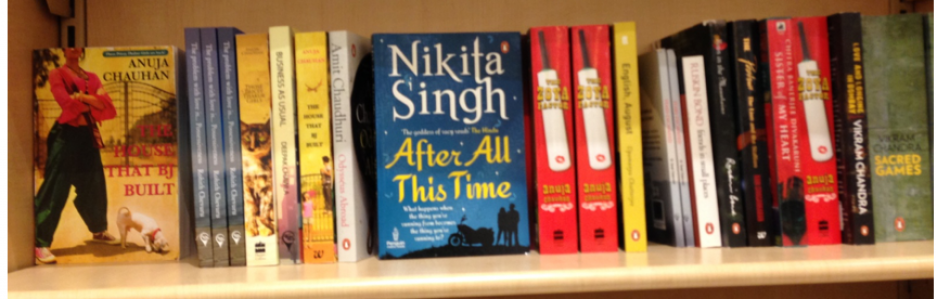

The silliness of the obstacles brings to mind some of the complaints I’ve heard about Anuja Chauhan’s The Zoya Factor, that Zoya’s insecurities go on too long. But in that case, there was at least a kernel of a genuine cause – Nikhil was a sophisticated superstar, Zoya a naive nobody but she had something that would would be very useful to him. And also in some ways it worked because it inverted a stereotype by making Zoya, or in the case of Jinni in Battle for Bittora, the insecure one.

The Wedding Photographer however turns on a stereotype that underpins the romance genre – the gold digger. The heroines task is to distinguish herself from this personna.

Tania Modleski in her classic study of the Harlequin novel, Loving with a Vengeance, has pointed out that a core dilemma for the romance heroine is to improve her class status while not only concealing that she is doing so, but by being genuinely guileless about the whole affair.

Risha aces this.

When she meets Arjun, she shocks the adversarial stewardess on the flight who is trying to unseat her by her cluelessness as to who she is sitting next to. She is more interested in his chocolate mousse than him.

She is gorgeous but unaware of it. She is seemingly sexually inexperienced. She adheres to her parents strict rules for her as a single woman in the city even though they are not around to check. She is down to earth to a fault.

In case we missed that this is where her attraction lies, Arjun explicitly tells us:

“Arjun couldn’t believe this girl. It was obvious she hadn’t know who he was at first, but now that she did, she didn’t seem intimidated by him in the least. Nor was she throwing herself at him.”

“The girl sitting next to him didn’t seem thrown off by his wealth or fame. If anything, she was amused by it. She teased him, laughed at him …”

“Risha seemed real. She had no idea how beautiful she was”

Mr Darcy would have been so proud. The above, however, are an argument for the “show not tell” School of writing if there ever was one.

Moreover, like Elizabeth in Pride and Prejudice, Risha distinguishes herself by her personality. She acquiesces to the air hostess’s demand that she vacate the business class seat she had been upgraded to because, she explains to Arjun, she didn’t pay for it. She seeks out the mother of the annoying boy who pooped in the seat next to hers and gave her a doctor recommendation.

As Arjun muses, “How many girls did he know that he could call nice”

Risha may not quite have Lizzie’s acerbic wit but she is good at what she does and committed to it in a way that impresses Arjun. Not just a pretty face then:

“Artistic without being pompous, beautiful without being overbearing, and filled with warm bring colours. Her photography, Arjun mused, was a bit like her personality”

Nancy Armstrong has noted how the 18th century domestic novels, starting with Daniel Defoe and Samuel Richardson and finding their finest expression in Austen and the Bronte sisters, masked a class coup. In these novels, middle-class women are shown as being deserving of approbation (signaled by marriage to an aristocratic man) due to their morality and quality of mind.

The implication here is that inner virtue is what distinguishes a person, not class, and that this distinction is not the province of the aristocratic class alone. In fact, aristocratic women are ridiculed for their superficiality. Think Caroline Bingley in Pride and Prejudice.

The 18th and 19th century writers deliberately chose female protagonists to make this argument – after Robinson Crusoe, Defoe found greater success with his novels featuring a woman as the central character – so as not to seem to be openly challenging the ruling class.

In Risha’s case, there’s a string of women she is contrasted with: she is not Krutika the bitchy and sexually aggressive stewardess, she is not the bored and entitled Divya Arjun’s mother wants to fix him up with, she is not Arjun’s ex-girlfriend Karishma who used her association with him to advance her career and then cheated on him (it is this Karishma we are asked to believe who causes him to suspect women in general and models and journalists in particular as manipulative).

And she gets along with his family. Arjun notes that she managed to charm both his formidable grandmother and his flighty mother. A scene of camaraderie between Risha and his sister literally bowls him over.

Meanwhile, what of our hero? He ticks all the usual romance hero boxes – handsome, rich(er than the heroine), masterful (in the opening section, he uses his status as wealthy, famous dude to cower admittedly annoying airbhostess into leaving Risha seated next to him).

He is also prone to fits of passion, grabbing Risha by the hand and commanding her to talk to him, which he admits is brutish behaviour but that must be presumably excused because it is Risha who inspires this. Ditto to smashing a glass in anger, which he then apologised to the cook about.

Because despite his privilege, he’s got the common touch, as heroes tend to. He demonstrates this by hugging the family driver during a cricket match.

In fact, mingling with the masses proves to be just the solution to his business problems – a workers strike that threatens to throw his affordable housing project off schedule. It is Risha who suggests that the workers just want to be seen as people and their protest may not really about money. And hey presto, it appears that all the workers wanted to do was to play cricket with the boss and take selfies with his national team vice-captain friend.

The strike, despite its glib treatment, is a reminder of where the wealth of the family in question comes from, wealth that is used to fund Arjun’s sisters lavish wedding. Early on in the novel, we are given the rundown of the events – a satsang in praise of the mother of the bride’s cult leader who is gifted (and whose venality is shown up later in the stolen photos episode), a mehndi ceremony, aretro video games night hosted by Arjun for the young people, a cricket match, cocktails and dinner, a choora ceremony in which the bridal bangles are put on, and finally the wedding itself. The latter events are held at a five-star hotel.

The wedding brings together generations – Nani drinks her grandsons off the table and correctly identifies Rishabh as gay but also educated the young people on the caste hierarchy (Khanna is higher than Kholi but Kapoor is trumps them all). The latter is dismissed as the foibles of an old lady but is clearly common enough a feature even at the weddings of the cosmopolitan elite to warrant mention.mThe wedding also brings together the family geographically with the proclivities of small town cousins providing comic relief.

All the couples in the novel do not dramatically break caste and class barriers. Risha May be from the middle class, but her caste is acceptable. Chinky’s husband Rohan are from different backgrounds / which is commented on by her mother, but Rohan compensate with his self-made wealth. Nidhi, Risha’s friend, and cricket star Vikram – whose story is the subject of an earlier book that I fully intend to read as soon as possible – are also from the same social circle.

In the end, Risha and Arjun overcome the odds, and admit their feelings for one another. What these odds are however turns out of be just Arjun’s on-and-off-again antipathy towards Rishathat is predicated on his fear that she will turn out to be a gold digger. Class continues to be a central conflict, if not the only, animating romance.

…

Which brings me back to Made in Heaven which I just finished watching. I finished the book in two days, but took a week to get through the series at my two episode per night on average pace.

The very first wedding featured is that of a middle-class nobody into an elite industrialist family. Tara and Arjun, the wedding planners, are asked to look into her background, and a problem is found that is a non-issue for the groom but a deal breaker for his parents, who one gets the feeling were looking for such an obstacle.

The situation is just a bit too close to home for Tara, who herself was a nobody who married into the elite. There is an awkward scene in that first episode in which the groom’s mother, played by the excellent Nina Gupta (ironically a woman who flouted the conventions of good Indian womanhood herself off screen) rants about her daughter-in-law-to-be calling her a gold digger before realising that Tara might not be the appropriate recipient of these comments. “Not you,” she qualifies. “You fit in very well.” Just how much Tara had to do to fit in and the hollow rewards of this labour are revealed through the series.

Made in Heaven is exceptional in how it eviscerates the grotesquery behind the glamour. Tara is the perfect daughter-in-law who combines the duties of Indian womanhood, calling her mother in law mummy without irony despite her constant barbs, with a hard-nosed head for business and impeccable style. But with her, we gradually see the toll being the pretender takes.

Nevertheless, in that first wedding, she tells the outraged bride to be to think smart, use the situation to her advantage and not throw away the fortune beckoning her. This is what Tara herself has done and refreshingly, we are not supposed to think any less of her.

At the end of the series, she realises that she will always be the outsider the world that Adil and her former best friend Faiza inhabit and that she’s sick of it.

The world that Adil and Faiza inhabit so seamlessly and that Tara has to work to fit into is milieu of Polite Soviet, Mahesh Rao’s retelling of Jane Austen’s Emma. When reading that novel, I wished we knew more about what happened to Dimple, Rao’s version of Harriet. Tara’s is that narrative.

***

Finally, a quick recap of why I think The Wedding Photographer falls into the broad romance, but not the chick lit, genre:

1. The romance heroine tends to be gorgeous, as Risha is. Apart from Arjun, we are told she has a number of admirers in the office. This is in contrast to the chick lit protagonist who is usually ordinary looking.

2. The OTT way both Risha and Arjun are described. For example:

“Her blush from her earlier embarrassment clung faintly to her cheeks, offsetting the olive undertones in her flawless skin and highlighting her full lips”

3. This OTT style of description carries on into their physical chemistry:

“He claimed her mouth in a long, ravenous kiss, igniting each nerve in her body, making her very skin come alive. She parted her lips, inviting his tongue in as he continued to kiss her greedily, passionately.”

This is straight out of Mills and Boon, rather than Bridget Jones’s Diary. As discussed in the post on The Wedding Date, extended descriptions of sexual activity are not common in chick lit.

***

Read an excerpt of The Wedding Photographer here.

Are you as obsessed with Made in Heaven as I am?