Title: Paper Moon

Author: Rehanna Munir

Published: November 2019

There are many thrills to reading Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, but a big part of my enjoyment of the novel was for the first time being immersed in a world that was familiar to me, the streets of which I had walked and food I had eaten. The novelty, but not the pleasure, of this wore off as Indian writing in English became a commonplace part of the literary landscape.

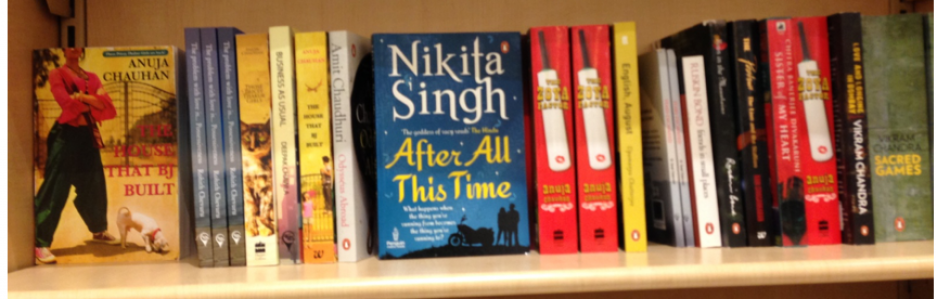

Popular literature in English, though, remained set in lands far away. That changed in the early 2000s; in my not so humble opinion, Anuja Chauhan is the finest example of popular writing in English. Much as I love Bridget Jones’s Diary (and I do love it), Chauhan gave me something I didn’t realise I needed: a romance novel in which I got all the in-jokes and references, set in my immediate reality.

Paper Moon takes this pleasure one step further. It is not only set in the city I grew up in, but in the very suburb in which I lived most of my life so that when Fiza picks out a location for her bookshop, I know exactly which bungalow she is referring to and can picture the building next door where a famous Bollywood actor (alluded to as Armaan Khan in the novel) actually lives; when Fiza speaks of eating a “frankie”, I can taste it because I know exactly the stall she is referring to.

The once-sleepy suburb of Bandra in which the novel is set is sometimes today to my irritation referred to as the “Brooklyn of Bombay” (as if any place can only be comprehended as a pale comparison of its American counterpart).* Munir, like me, grew up in Bandra and knows its bylanes and lore (think Zahra beauty parlour with its massive portrait of legendary actress Rekha). The novel is an ode to Bandra, capturing both its Brooklynisation (of which Fiza’s bookshop is perhaps a part) and more down-to-earth vibe of coconut sellers and convent schools and aunties who are free with their advice.

The novel opens in St Xavier’s College, where both Munir and I earned our Bachelor’s. In fact, Munir and I were at Xavier’s at the same time and studied in the same English literature classroom under the redoubtable professor and poet Eunice de Souza, who appears in the novel as Frances D’Monte. The novel is dedicated to her.*

Fiza, Paper Moon’s protagonist, whose trajectory like that of many chick lit protagonists, shares many similarities with the novel’s author, compares Frances/Eunice to the titular figure of Muriel Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie:

If you were one of her chosen ones in a classroom – like the crème de la crème of Miss Jean Brodie – the three years you spent studying Eng Lit would be life-changing. Fiza was one of the chosen few – the one to whom Frances gifted postcards from the Bombay Natural History Society, whom she treated to the occasional chicken omelette at Tea Centre in Churchgate, and even rang on the phone to ask if a particular lecture had gone well for the class.

Munir was part of Eunice’s coterie of ‘chosen ones’. I never was, though obviously, like everyone else in her classrooom, I yearned to be. I blew the one chance (I fantasise) of ever developing a relationship with her beyond the usual teacher-student pleasantries. The fact is I was too awestruck to behave coherently around her.*

I always wondered how Munir and the other students who could count themselves among Eunice’s friends managed it. Reading this book, that mystery is somewhat solved. It wasn’t that they lost their awe of her; they just managed it better (and, of course, she saw something in them).

Eunice told us we weren’t studying English literature to sell Binaca toothpaste (at the time, Binaca wasn’t even very popular so the insult was doubled), yet many of us went on to do just that (although with some part of us forever altered by having sat in her classroom). Munir, however, went on to start a bookshop, a process chronicled in the novel.

One of the criticisms of chick lit is that it uses the protagonist’s career as not much else than a backdrop for romance. This is not entirely true – there is a sub-genre “worklit” – best exemplified by The Devil Wears Prada – that puts the workplace front and centre. The further criticism is that (in Western chick lit) these careers tend to be in the media. While I’m not sure what the problem with media-related careers is, it is likely that a good number of people who land up in the media fancy they have a book in them.

Indian chick lit, however, describes a far greater range of careers – from the media staples to finance and the army – and the workplace is much more than a backdrop, even if the protagonists do seem to bumble through just like their sisters in chick lit in the West.

At one end of the chick lit career spectrum is the fashion job, at the other end, I would contend, is not the soulless management/finance/consulting job, but the bookshop that Fiza/Munir runs/ran. Many serious readers fantasise about writing a novel and/or running a bookshop. Munir has had the pleasure of both.

In Paper Moon, through Fiza, she tells us how in a fair bit of detail: there is some serendipity, much pleasure and a great deal of management-type stuff (like making a business plan, stocking and invoicing, and marketing). Nevertheless, because this is a book set in a bookshop, there are a myriad references to books and literature. It is a book about books and the people who love them.

If romance in its original form is a quest, in Paper Moon, this quest is for the success of the bookshop. The novel shares its title with the name Fiza chooses for her bookshop, a reference to the song Blanche in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire sings as she bathes, even as her dreams are being ripped apart by her brother-in-law outside the bathroom door. The lyrics of the Nat King Cole classic It’s Only A Paper Moon and Blanche’s evocation of them allude to the transformative power of love, its ability to imbue the world with meaning:

You say it’s only a paper moon

Sailing over a cardboard sea

But it wouldn’t be make believe if you believed in me

Essentially, the fairtytale fantasy, specifically the Sleeping Beauty fantasy: the maiden sleeps, until the prince arrives and with a kiss wakes her into real life. Helene Cisoux has pointed out that this is the roadmap for life that girls are sold.

Interestingly, the song is one that Fiza’s formidable mother Noor (more on her later) used to hum. Noor’s, like Blanche’s, story is riven by love gone bad; it is love that turns out to illusive and life the pieces that must be picked up in its aftermath.

Love is also the paper moon hanging over Fiza’s narrative. There are two men in her life – Dhruv, her ex boyfriend, and Iqbal, the laconic artist who pops in an out of the story. I found Dhruv somewhat interesting but Iqbal a not quite convincing character. As Fiza is increasingly drawn to Iqbal, he seems to be like a “paper moon” figure, one that I cannot entirely believe in. In some ways, Iqbal corresponds to chick lit’s older, wiser, more suave, richer Mr Big character (down to the commitment phobia) but Munir writes into his life real complications that our young protagonist must decide if she can live with.

The heart of the novel, however, is the bookshop itself, and whether Fiza can sustain this venture. The men drift in and out, but the relationship that the reader is invested in is the one between Fiza and her bookshop, and through the bookshop, between Fiza and herself. Because the bookshop proves to be a Pandora’s box: first, by opening up the wound of Fiza’s father walking out on their family and the discovery of his other life, then by staging her romantic dilemmas and finally as the site of closure.

Freud tells us that at the heart of Western religion and the family is the myth of the son slaying the father so that Western civilisation is shot through with primal guilt. His Electra Complex was never so convincing as his Oedipal theory, but we can all agree that “daddy issues” are a thing.

Less attention has been given to the mother-daughter relationship, but feminist philosophers and psychologists such as Luce Irigaray and Nancy Chodorow have tried to rectify this. They have argued that it is the mother, not the father, who is the central love object for the girl.

When studying Indian chick lit for my PhD, I discovered the recurrence of an absent father/over-present mother trope. Paper Moon is no exception. The reemergence of the spectre of the father shatters the delicate balance of the relationship between Fiza and her tempestuous mother Noor.

Psychologist Sudhir Kakkar has noted that Indian girls remain attached to their mothers for a long time; they are weaned later and remain tied to their mother’s apron strings right up to adolescence when suddenly the relationship takes a harsher turn. When an Indian girl hits puberty, her mother must begin to prepare her for marriage, thus becoming the dispenser of patriarchal wisdom.

In most Indian chick lit, this takes the form of the mother exhorting the daughter to marry and to conform to some monolithic idea of Indian tradition in order to do so. The mother-daughter conversations become an articulation of the daughter talking back to tradition and resisting its claims. Even so, it remains a conversation that is grounded in affection and one that does not cease. The umbilical cord is never really severed between and Indian woman and her mother, even if that cord becomes a telephone line in Indian chick lit.

Some novels, however, present a variation. The mother herself does not conform to tradition. An example is the mother in Meenakshi Reddy Madhavan’s You Are Here, one of the rare Indian chick lit novels in which the mother is named and not just referred to as some variation of “Ma”. I hypothesised that by rewriting mothers in chick lit, we might also change where daughters end up. Paper Moon is an example of this.

Like Abha in You Are Here, Noor in Paper Moon is divorced and has built an independent and somewhat unconventional life for herself. But this does not lead to abandonment of the daughter. The mother-daughter bond remains extremely close. In Paper Moon, Fiza must revisit her relationship with her mother to reclaim her paternal history, but this is far from a severance.

Moreover, Noor, like Abha in You Are Here, is far from concerned about her daughter’s romantic future. Her reconciliation with her daughter comes in her acceptance of the dream of the bookshop and in lending it her support.

If marriage is about channelling fertility and reproduction, Fiza fulfils these through the bookshop. The second half of the novel is more concerned with resolving Fiza’s romantic dilemmas and I found it less engaging than the first half which is about setting up the bookshop. Whether Fiza ends up with a man or not becomes a sub-plot that is not necessary to neatly tie up.

Rather, Fiza – and the reader’s – romantic closure will come with the bookshop itself. By the end of the novel, Fiza has not only built a home but created a family in her store. The only thing left to do is to proliferate.

*I have not yet got over being told, to my outrage, by a yuppie thirtysomething mansplainer that I did not know Bandra if I had not been to the restaurant Barbecue Nation.

**Eunice in her lone foray into fiction also wrote a novel about a single woman in the city – Dangerlok. A review of E. Dawson Varughese’s Reading New India: Post-Millennial Indian Fiction in English, which discusses Indian chick lit, points out that Varughese seems unaware of Eunice’s work. The fact is that Eunice herself was not the first nor the last writer to deal with this subject. What sets Indian chick lit apart is the tone. Reading Paper Moon side by side with Dangerlok would elucidate the differences, even though Paper Moon isn’t a classic chick lit text.

***A few years ago, a young man stopped me in the street and asked me who was one prominent person I would like to have lunch with and that his NGO would arrange it if I could dedicate a certain number of hours to volunteering for a charity. I found that I could not think of one person I really wanted to have lunch with – and now I realise, I should have named Eunice.